The texts of Simple Susbtraction have been written under hypnosis and with the help of a deck of Oblique Strategies cards.

My texts are sometimes written in the context of exhibition projects, in these cases, the texts are made available to the spectators in the same spaces of the exhibitions. My texts can also be independent works and be read during public readings or published in publications.

I had already tried working in a hypnotic state (self-hypnosis) in the series of photographs called Présence II “Le Grand Sans-abri.” In this work the process is extended to include texts. The idea behind Simple Soustraction is to achieve a state in which the mind fluidly liberates images and visions that are then transcribed as texts. The mind in this case is a site like any other for capturing images, as a photographer does in reality.

In order to not crystalize the experience of vision, Le Grand Sans-abri had incorporated a kind of movement in comprehending still images through the juxtaposition of several distinct images at the same time. So, too, in Simple Soustraction the images are part of the movement thanks to a form of narrative. The texts, which take the form of short stories, are to be understood in the end as devices in which the question of the image (and of the sculpture-object) can be developed in multiple ways, including self-reflexively.

Self-hypnosis

The technique of self-hypnosis introduces a deep calm that allows the brain to produce images (visions) extremely freely. The hypnotic state can also be considered a site, a place, that the hypnotized returns to at each session. At that point, he can, in a way, develop it as he pleases. In that regard, “Simple Soustraction” is a constructed space like a work of art.

Stratégies Obliques

Oblique Strategies is a deck of cards created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt in 1975. Each of the cards in the deck bears a kind of mysterious and arbitrary injunction. Eno used the deck during recording sessions to prepare artists and push them to break up creative habits.

At the start of each of the writing sessions under hypnosis that make up Simple Susbtraction (or Simple Subtraction, the title is borrowed from one of the cards in the deck), one or more cards are drawn from the Oblique Strategies deck. This method ensures that the start of each experiment is not consciously chosen.

……………….........................................

Ambiguity Where Unforgotten Death

By boat, the crossing hardly lasted ten minutes. But that morning, it seemed to me the trip took much longer. I was in the habit of standing on the forward deck and from there staring at the prow tirelessly cleaving the waves like scissors cutting through a giant sheet of paper.

The gallery stood a few blocks from Port-Noir in a residential neighborhood. A limousine was parked in front of the vast window, on which the title of the show, “Ambiguity Where Unforgotten Death” (Ambiguity or the Unforgotten Dead), was written in large white letters. A metal door opened to a corridor that led to a reception desk. No one was seated in the two chairs hidden behind the counter, which was piled with invitations and binders filled with documentation. Nevertheless I heard a “hello,” which must have been addressed to me, emanating from another room, perhaps a back office. Crossing the threshold separating the reception from the exhibition galleries, I folded and tucked away in my jacket pocket the introductory text of this rather mysteriously titled event.

The space was bathed in a half-light. The blinds on the windows had been lowered and tilted. Here and there the half-light was slashed by series of long streaks of light. The venue was completely empty save for a small photograph hanging on one of the gallery walls. I heard my steps echoing in the room as I moved in closer.

The image in a vertical format was displayed in a skeleton key. Exaggeratedly large, the key seemed to want to distance the image as much as possible from the wall, perhaps with the aim of emphasizing in a deep and, in the end, illusory way the world separating them. For the frame they had chosen a thin polished aluminum rod that gleamed slightly and gave off a few flashes of light in the darkened space of the gallery. This type of frame, used more in hotels and restaurants, flanked by slightly kitsch posters, raised a slight doubt here in the viewer as to the status of the work of art in front of him.

It wasn’t easy to make out what was shown on the photograph since the glass protecting it gave off a multitude of reflections coming as much from the direct light of the windows opposite it as from the indirect light thrown off by the other gallery walls. The darkness, a bit deeper as well in that part of the gallery, meant additional difficulty for someone who might want to see something there.

Paradoxically, these glints, cuts and other accidents of light—this collection of revealed visual events on an image that was indeed resisting our gaze proved to be in itself an intriguing situation. Was that the work of this show in the end?

Other elements also drew my attention. First, it was a ghost image. One, then two eyes, then part of a forehead, slowly emerged from an indistinct mass. The image vanished, then returned. It appeared in a more precise way on the glass before an especially dark area of the photograph. I now had before me a kind of expressionist-styled portrait. This sharply contrasting black-and-white image reminded me of those Scandinavian photographers at the turn of the twentieth century who lit their models in an astonishing, almost unreal way. That face was mine of course, but the image (can one speak of image here? Of vision?) that I saw was located in an in-between space that I had a hard time defining and which remained between photography, the glass, myself, and the venue around me. “Here’s what images and exhibitions are good for in the end!” I said to myself, “For revealing to us the viewers and the world around us!”

A glint on the glass intrigued me; the unity of the vision with the portrait was immediately rent. With this new element my eye set off once again on a path that should lead it to construct a new image. That image would crystalize at the end of a movement, a back-and-forth oscillation, then a fusion between my mind, imagination, and the real environment around me.

I concentrated on that trace of light. My eyes, dazzled at first, eventually adapted to it like a camera on which you closed the aperture a little. On the white surface there were details now, like little horizontal white lines. These were moving, undulating on a glistening surface that seemed horizontal. Those movements, like tremors, pleasantly hypnotized me. Lulled I lingered a few minutes before this abstract picture, this intoxicating all-over painting, little by little losing all notion of space and time. The dark shape of a boat appeared; it disrupted the shapes around it, jostled them. The lake, through the slats of the blinds behind me, was evidently reflected on the glass covering the photograph. I thought I could also make out the shore where I had just disembarked a few moments before. Nevertheless, I was suddenly prey to a doubt. Was I seeing these things really, or was I seeing them because I knew they could potentially be there, or even because I had seen them previously? Just how much was my mind, helped by its memory and imagination, completing the hints, the chaotic fragments of reality in order to distil a simple and intelligible image?

I turned on my heels with the aim of leaving. Before my eyes the overexposed image of the lake was floating still, indistinct, this time on one of the empty walls of the gallery. I lowered my eyes a moment. Then quickly, without making a sound, I returned to the reception.

Martin Widmer, reading, "Simple Soustraction", 2016

Martin Widmer, reading, "Simple Soustraction", 2016

……………….........................................

Painting

The painter knows intuitively that the picture is completed. His hand slowly slides up along the wall. Tiny drips of black paint leave the floor and return to the brush he’s holding, almost on the tips of his fingers. Suddenly, following a broad gesture begun by the wrist, the brush cuts across the canvas from top to bottom and erases the black line. Then the artist approaches the right side of the painting and removes short sinewy lines, like hatching, one by one. The painter exchanges his brush for a mid-sized one and energetically attacks the large beige-colored shapes that extend over the entire lower part of the work. He automatically dips the brush in a can of paint, then puts it away directly in one of the glass jars that have pride of place on the tray of a small metal cart.

The artist steps back a few meters and takes a mobile phone out of his pocket. He stares at its screen for a long time before taking a few photographs of his painting.

Having got a can of spray paint, the man comes back and approaches the wall so as to press his back to the surface of the canvas. And then, as if he were performing some sort of choreography, he stretches out his arm and traces, from right to left, partial circles in the space behind him. Thick clouds of white paint are extracted from the painting with each movement and rush in perfect formation into the minuscule hole of the spray can. The painter frees himself from the painting and squats; he reaches out to grab another spray can that is standing on a small stool. After hesitating between the two cans, they set both on the studio floor.

The artist removes a large shape, cut from the canvas, which was glued to the painting. This piece of slightly coarse fabric is laid out on a plastic tarp directly on the floor and covered with paste. Afterwards the piece joins the surface of another picture that was lying on the floor of the studio.

The painting is taken down from the gallery wall and laid flat on a table. The painter grabs a stapler and removes the canvas from the stretcher. The canvas is then appended to another much longer piece of canvas by using scissors. The whole length of cloth is carefully put away in a metal cabinet.

On the table, between the empty spaces of the stretcher’s structure, the artist scribbles a few sketches on A4 sheets of paper. Among the drawings that are piling up lies an open book. On the double page that can be seen, the painter underlines sentences with a yellow felt-tip pen. After bending over the work for quite some time, he closes it and slips it a little further away into a small bookcase. The stretcher of the painting is completely dismantled. Using a cutter, the man joins lengths of string wrapped around the pieces of wood to make a bundle, which he sets next to the studio door. He eventually sits on a chair and gently takes his head in his hands.

Before these eyes the mental image of the painting disappeared. The vision isn’t stable and the painter has to concentrate to be able to observe it for more than a few seconds. He is increasingly disturbed by images from his daily life: the face of a child, a secondary road, dead bodies in the dunes of some desert glimpsed in the evening news.

The work is now clearly visible in his mind. A piece of untreated canvas is stuck to its surface. Its shape, an oval at the bottom of which a small squiggle of the fabric is poking out on the left, vaguely suggests a comic book speech balloon. Over the whole of the picture a coat of semi-opaque white paint has been applied with a sprayer. On the lower part of the canvas, a large beige shape has been quickly sketched out using a heavily diluted paint. Black vertical lines cross the painting. Yet all at once, the artist is no longer sure if it’s a matter of one or two lines, since everything is momentarily mixed up. Above on the right, a torn sheet of paper has been simply scotch-taped. Black lines of paint, hatching really, have been added as if to cross out the drawing of a small airplane that was done in a bit of a childish hand and is now scribbled over.

The vision of the painting wavers. Several different works are becoming mixed up in the painter’s mind. Ropes cross spaces, parts of Donald Judd sculptures pierce various paintings and are projected onto the bluish gallery walls, and finally it’s the image of a dog that comes to the fore.

The painter extricates himself from his thoughts, rises, and takes the cup of coffee that has been set next to him. He takes a sip of the liquid, which seems cold. Into the Italian coffee maker he pours the contents of his cup. He puts on his jacket and leaves the studio. In the rearview mirror of the still half-open car door, the man notices the gaunt silhouette of a dog. Motionless, it is staring at a face it doesn’t understand in the little bit of mirror. After turning its head several times toward the studio door, the animal suddenly jumps up and disappears.

……………….........................................

Neo Geography II

The interior of the plane was much bigger than what I had imagined. Whenever I dragged myself out of my seat to verify, once again, that my luggage was well placed in the overhead compartment, I thought about the time we took to pack our luggage, the care with which we slipped into our suitcases the objects and diverse documents which we carried with us for the exhibition. What in our belongings could have aroused the curiosity of security agents a bit too much had been hidden as best as we could. For nothing was illegal, if no object broke the law, some of our suitcases should not have been searched. How could we have explained, for instance, in a simple and convincing manner, the documents pertaining to the corpse?

It was the first time we used a Mental Map project management protocol. The version we had chosen allowed for the management of the different types of spaces entailed, be they physical, digital, or mental. In this way, our minds, our computers et mobile phones, diverse networks including the web, physical such as the CAN in Neuchâtel, Post Territory Ujeongguk in Seoul, as well as all the intermediary spaces including airports, planes and the diverse means of transportation were thereby connected so as to form one and the same space, a territory, a mental geography, which would exist in our heads only for the duration of this project. This construction was shared collectively thanks to spaces arranged in our brains and which communicated between each other. Self-hypnosis techniques enabled everyone to maintain its viability.

As the protocol invited us to do, journeys by plane between Switzerland and Korea had been carefully prepared. We had unearthed a plan of the aircraft that accurately detailed all the parts of the Boeing 747 the Korean company was using. In addition to a general plan, it contained several perspective drawings that included the main parts of the aircraft with passengers’ compartments, as well as various cabins and baggage holds. We gained a very precise knowledge of the craft to the point of being able, by closing our eyes, to wander virtually and in a fluid manner, within the meanders aeroplane. And so, together we had organized our journey. There was no difference for us between art centres and other places, we treated them on the same level, they were part of the same great exhibition.

The protocol imposed numerous constraints such as protecting ourselves from those external conditionings which could destabilize it and weaken its structure. By mutual agreement we kept ourselves distant from the news, especially from worrisome news related to the situation between the two Koreas. The stakes were little known to Europeans. With the help of messages conveying simplistic concepts, Western media had the habit of imposing a certain world vision from which we wanted to protect ourselves at all costs. Thought had become a place of resistance, and the fiction in which we had all decided to evolve was a political act, the only one that still seemed to be interesting to try.

Korean artists had, for their part, an entirely different way of contemplating their situation. During the many discussions held which addressed art as much as political issues we noticed how limited to communicate as well as incapable of conveying the subtle nuances of our remarks the international English we used was. Paradoxically, this very difficulty gave us the idea to create a new common space and to use a protocol. It had to be conceived based on entirely new concepts. To do so, terms such as: space, geography, site had to be reformulated as their meanings eventually seemed quite different from one culture to the other. This idea found an echo in the research carried by Hyungmin Pai the director of the Seoul Biennale as well as in the conversation held with him subsequently which eventually bonded all the participants around this idea.

The conference he gave as part of the first exhibition will remain an important moment for all of us. First of all, it was one of the few moments when we were all reunited, physically, in the same space. Impassively, we looked at the giant screen on which architectural images were projected. I still remember having looked lengthily at our faces. They were backlit by the light coming from the screen and distinctly detached themselves from semi-darkness the prevailed in this place. When some people brought their phones in front of them to film or take photographs, their faces got even brighter. Almost instantly, what was captured was posted on various social networks and we could them appearing in each other’s applications.

All of us succumbed to the charms of the black and white photographs of Korean architect Ahn Young Bae that Hyungmin Pai screened. How many of us, carried away by their fictional powers, found themselves teleported to the magnificent interior courtyard of Buseoksa Temple. How many crossed it and heard squeaking under their feet the small pebbles one could figure out on the old pictures. Who could today, and with the words of which language, clearly and convincingly describe how, at this precise moment, space and time unfolded?

…

The plane landed. I looked around me in the hope of recognizing someone. There was nobody. A doubt occurred to me, had we all finally taken the same plane? I closed my eyes. In my head, something opened itself. I saw a space. Then artworks. Sounds came to me, words that spoke of exile, they seemed to come from behind me. I glided further away, floated for a moment above a set of metal grids. Then something cold stuck itself to my skin. A smell of beast also, of carrion, filled in the space. A second door. The airport. Through yellow windows, I saw lamps hanging over long masts throw their lights onto a décor which could have been found anywhere and which, in that case, was nowhere to be found. I let myself carried by a treadmill. Bizarrely, some parts in my environment were blurry. As if by reflex, I took my glasses off so as to find, somewhere, a button which would have them made function properly but, there was none. Then, by reminiscence, I remembered the project, Korea, exhibitions, I also remembered the story of the protocol, ideas and hopes about new ways of thinking about space, geography and time.

……………….........................................

They left their vehicle nonchalantly parked across a sidewalk that ran along the Parc de la Grange. Further on, they rushed down Boulevard de Montchoisy. In the car, the twalk had been lively, the stories, anecdotes, and ideas had come thick and fast. They all saw the things they were talking about in a similar way, distinctly, too, as if they were being screen around them. That kind of common view, which developed over the years, was the basis of their friendship. Like a litany, their sentences inevitably ended with a “you see?” that would be immediately validated by the group as a whole.

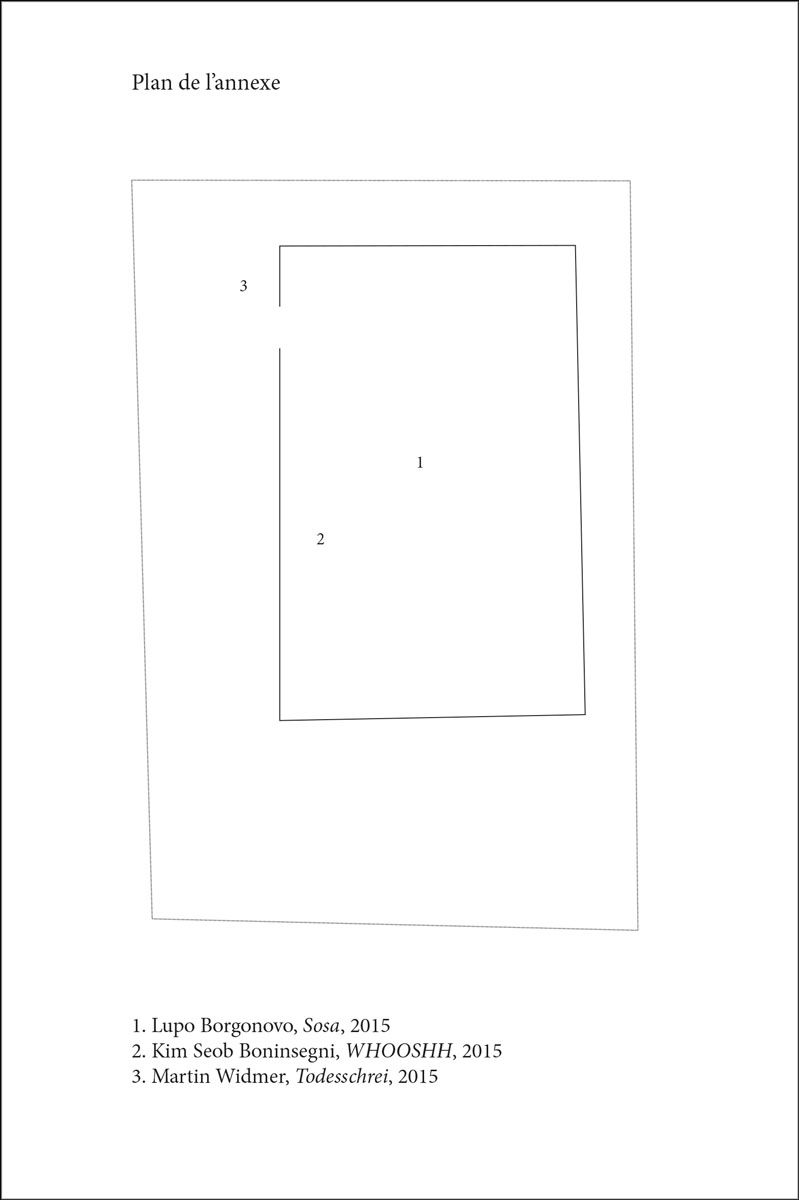

Walking on the asphalt now, they were silent. Their bodies, on the other hand, seem to have synchronized and, without really marching in lock step, without really developing a rhythm in common, the totality of their movements worked a kind of coherent choreography. The group at that moment was unconsciously expressing through their bodies certain things that had been said previously in words. They had been given the key to the gallery annex a few hours earlier. They were firmly resolved that evening to stay longer than they had the earlier times.

They walked around and around in the Eaux-Vives neighborhood for a long time. As is often the case when looking for the spot, they got lost. How many times had they thought they had seen in the distance the building’s door, then having walked towards it, the spot would lose, as they drew closer, the resemblance it seemed to have had with the one they were looking for. Yet nobody ever really worried about the situation. The loss of bearings, the fatigue which ended up tagging along with that random walk was part of a kind of ritual that would lead them, when they no longer expected it, to find the door of the gallery annex in a street where they could have sworn they would never have imagined it to be.

...

Decorated with the image of a peacock engraved in a chrome-plated metal plaque, the door opened to a hall flanked on both sides by two broad staircases. Yes, its façade was what you would see on a banal bourgeois-type building while its interior architecture was clearly more baroque. The lines, angles, thresholds that delineated and defined the volumes and separated the different spaces had been systematically doubled and shifted slightly out of line, creating a most odd effect, a feeling of movement and unsteadiness. The building then seemed to be kept in a kind of infinite trembling, and if one had wanted to use a metaphor linked to photography, one would have said that the building seemed blurred.

On a floor higher up, the group stopped before a glass door. Someone got out a key from their pocket and it was slipped into the lock hidden beneath a small cover on the left of the door. A mechanism emitted a slight metallic sound, then the entire expanse of glass slid away, disappearing completely into the wall. When the last of them crossed the threshold, it shut automatically. The gallery annex was a large indoor pool that had stood empty ever since the gallery had begun mounting exhibitions there. The basin, some twenty meters long and a dozen wide, offered an original space for putting together those kinds of events. The main gallery was in fact much smaller than its annex. On the other hand, the latter, given its location smack in the middle of a private building, could not claim to be a space that was officially open to the public. For this reason, the place had an ambiguous status and nobody dared to speak about it as if it really existed. Over the entire right side of the space, broad picture windows offered a unique panorama of the city of Geneva. On the horizon, amid ghostly towers, a kind of dark puddle could be seen in which the writing of neon lights was abstractly reflected. It was the lake. It looked so far away.

The group contemplated the space of the pool from its edge. They had this odd impression of finding themselves above the show and contemplating it as if they were studying its layout on one of those A4 sheets that are made available in all exhibition venues. At the center of the pool an artist had deposited an imposing pile of stones. They were exaggeratedly large and most certainly fake. Together these stones formed a giant head, a bit like the way the painter Arcimboldo did with vegetables and various foodstuffs. The more the group looked at this sculpture, the more they noticed that each stone making it up had been precisely designed. The eyes were two perfectly round cavities whose diameter would allow a person to slip through. As if hypnotized, they remained a long time looking at those two gaping holes. Inexorably the eyes of the sculpture seemed to want to suck them in, and while someone did mention the urge to climb down and disappear wholly into one of the eye sockets, no one moved in the end.

In the space of the basin, winding around the stone head was another work of art made up of numerous rubber tubes. These wide tubes ran to an aluminum tank in one of the basin’s corners. The group took one of the small side ladders and hardly had they set foot on the bottom of the pool when they heard noises coming from the installation. Indeed, sounds, sorts of soft, wet “whooshes,” were regularly issuing from the tubes. They then noticed the shapes that were traveling inside the tubes. Slightly bigger than the tubes, they formed, when they passed, slight bulges that produced that very peculiar sound. Without being absolutely certain, someone thought they recognized in this installation one of those fish cannons used in Canada to help salmon clear various obstacles. They counted a dozen shapes circulating around them in the many entwined lengths of tubes, which proved to work in a closed circuit. Eventually they indulged in imagining for a moment that together the sounds coming from this piece ended up creating the ambiance by the sea or some lake, a sound of waves and surf. Then the thought they were surrounded by probably dead animals suddenly chilled them.

The door, which led to a second exhibition space, was located on one of the basin’s sides. A tube running through it propped it half open. The space within was a wide corridor that went completely around the pool. It was plunged in darkness. A tube wound its way through most of the space, giving off “whoosssshes” that took on a tragic dimension because of the echoes. Another sound, less loud but fuller, was also being piped in. That audible field was the sound of an orchestra. All its instruments were playing a full cord at the same time that seemed to contain the twelve sounds of the harmonic scale and this was being done without any variation whatsoever. Above this layer of infinite depth, the cry of an opera singer could be heard. Like the music of the orchestra, this cry had neither a beginning nor an end, and the imminent death it seemed to have always been announcing would never come.

None of them had spoken a word for many long minutes. Their eyes had hardly ever met. The group encountered the works featured in the exhibition in silence, as if they formed an indivisible entity. When one of them tripped on the tubes, each felt the fall as if they themselves had taken the spill. Similarly, they sensed together that their visit was coming to an end and that the experience of that exhibition would continue immediately elsewhere, in other spaces and at other times. Later in their heads, they knew the sounds would come back. Later in their heads, they knew that the images of the tubes, the stones, later in their heads words like “fish,” words like “stone,” would also visit them. Later in their heads, words, phrases, images born here will form phrases will form words still. Later some will doubt what they have seen here. Later some will still see in their head the pool. Others will still perceive that cry which they never heard.

They returned to the car. The wind and the rain had spread a layer of leaves and twigs upon its hood. They quickly crossed the city to return the keys they had been entrusted with, but also in the hope of seeing the artworks displayed in the main space of the gallery. But they had lingered too long in the annex; they found the door was shut. A note, however, had been stuck up there addressed to them.

Martin Widmer, 2015

……………….........................................

……………….........................................